Empowering Minds:

A favorite bit of advice that I have acquired throughout life has been to teach others what you wish you had known. As a teen in the early 1990s, I began to struggle with anxiety.

The most obvious issue to my parents was my anxiety over making phone calls. I’ve never enjoyed speaking on the phone, but intensely loathed the effort it took to call a stranger for any reason, like ordering pizza.

This manifested itself one evening when I wanted pizza for dinner. My mother, thinking she was sly, said, “If you place the order, we can have pizza.”

Mom knew I would not be willing to place that phone call, even for my favorite food. Luckily, it was easy to convince my boyfriend to place the call. Though this is a simple example of one way that anxiety began to affect me, it became more serious over time.

Like many people with anxiety, I developed tension headaches and neck pain. I also began having recurring dreams about high-anxiety situations and loved ones dying. I coped, rather poorly, with what I thought were typical life struggles. Binge eating high caloric foods late at night, avoiding stress inducing tasks, conversations and decisions became regular habits. All of which only served to cause more stress and feeling like I was fundamentally incapable of managing what everyone else seemed to easily do. I developed a harsh and critical inner voice, chastising myself for my perceived failings and character flaws. Had I known then what I know now, I might have avoided over two decades of cyclical anxiety, depression and significant weight gain.

My mission to spread mental fitness knowledge began in the isolated days of the pandemic in the fall of 2020 while teaching remotely. During what I fondly call the “before times,” I was aware of only some of the mental health problems of my students, though I am sure there were people suffering silently as I had during my time in school. That fall, however, I became aware of far too many of my kids in crisis. For the first time while teaching honors students, I had kids skipping exams, missing class and failing grades in the double digits.

Encouraged by my district administration, I began to address aspects of the advanced placement psychology curriculum. Using mini-lessons in advanced placement World Studies, I reached out to kids who were hurting. I understood the anxiety and depression the students were displaying, and I knew they badly needed the knowledge that I wish someone had shared with me as a teen.

In the years since I first began the mini-lessons, the need for them has been reinforced as our nation is faced with a mental health crisis in our youth. When experiencing distressing emotions, kids generally seem to think in one of two ways. The mindset typically displays as either “Everybody goes through this, I’m not special,” or “No one else feels this way and nothing can be done about it.” Both thought processes lead to isolation and, for some, acts of desperation. It is vital that we help adolescents gain a sense of agency over their emotional responses to their environment. One way or another, kids will find a way to cope. They need information to ensure their methods of coping are healthy and lifelong rather than maladaptive and short-term. This is just as important for thriving kids as for those who struggle.

Periodically throughout the year in all of my courses, we spend five to ten minutes at the start of class on a specific topic of prevention education related to mental fitness. I explain to students, “Today will be the beginning of a series of lessons, scattered across the school calendar, to address a knowledge and skill set which I call mental fitness. It is a state of well-being and having a positive sense of how we think, feel and act.”

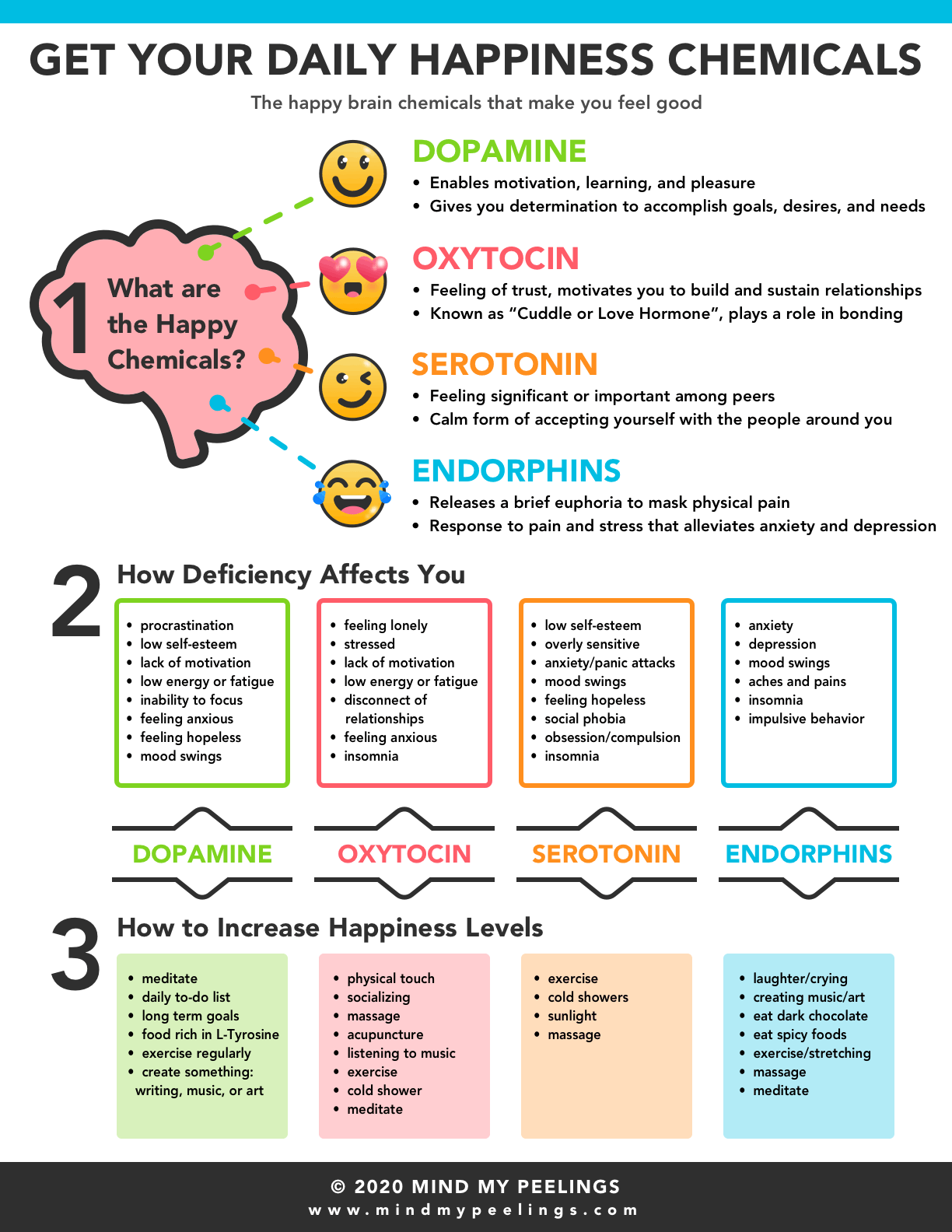

The first lesson explains that mental fitness is like physical fitness - the more you practice it, the stronger you are. The better you get at doing it, the more it helps. Just like how people prefer various ways of exercising, some tips to practice mental fitness might be preferable or more beneficial to different people. Mindfulness and mindful meditation are very helpful for me, but someone else might prefer to journal or go on a hike. The lessons have addressed topics such as anger, time management, stress, sadness and even difficult social conversations. Usually, any given lesson will be a singular graphic or slide that is explained including examples from my own experiences or those with whom I have crossed paths. An early lesson includes a graphic demonstrating activities that help to release different kinds of neurotransmitters.

Along with that information, there would be a couple of discussion questions: What are you doing to take care of yourself? Who or what can help you meet these needs?

Kids are introduced to neurotransmitters and activities that can help activate those “feel good chemicals” in times of need. They also build a strategy for maintenance of good mental health practices.

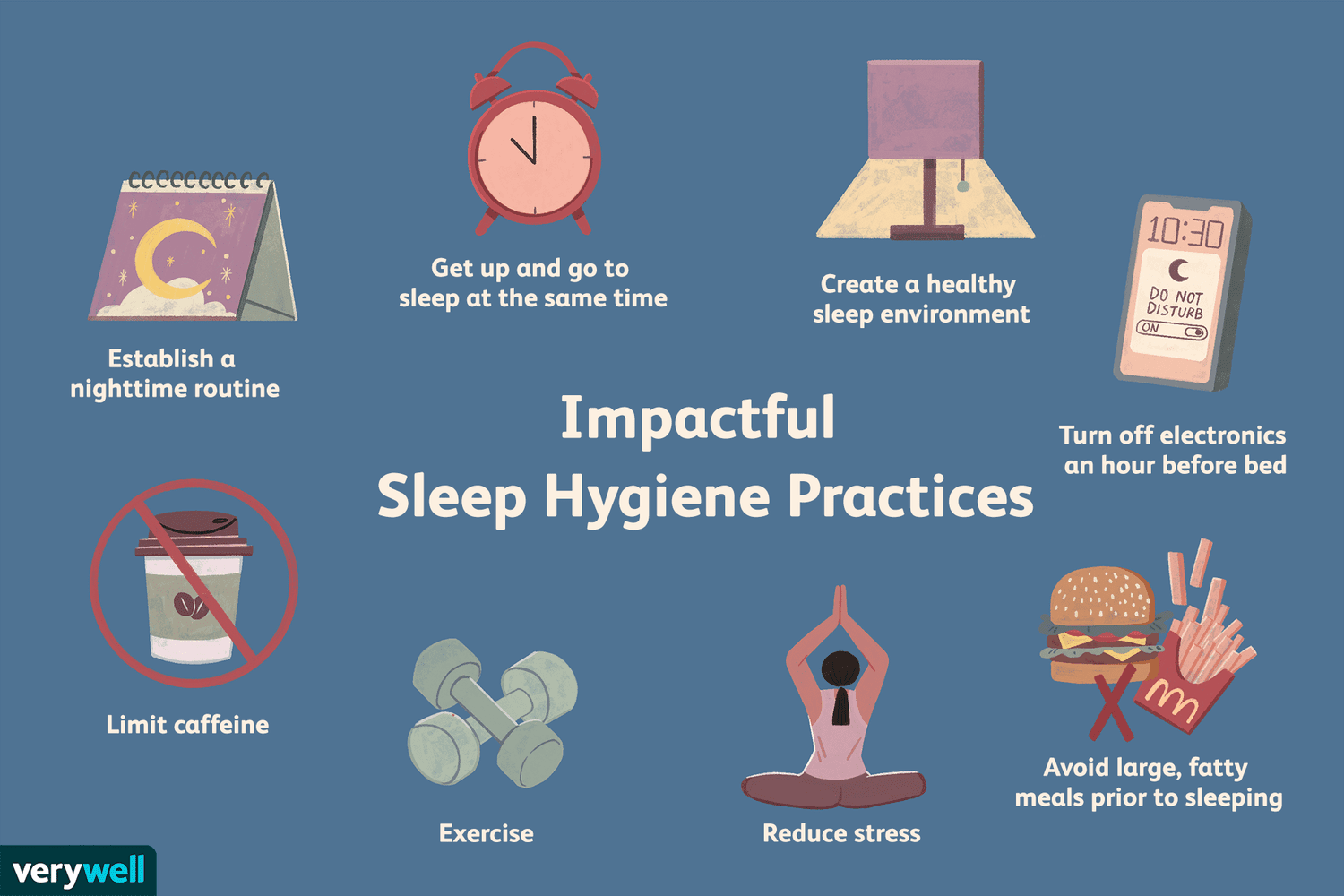

When it comes to healthy sleep habits, adolescents frequently struggle and do not realize the connection between ample sleep and mental fitness. We have all known those students for whom remaining awake in class is a struggle. I usually receive chuckles from kids when stating they should sleep at least seven to nine hours each night. They have homework, most likely work a job, lead clubs or practice athletic activities, etc. Our culture’s sleep debt habits begin in adolescence and escalate into college and careers. Kids are regularly sleep deprived and yet we are all familiar with the cranky toddler in desperate need of a nap. I encourage the kids to consider how a lower tolerance to frustration due to being tired can lead to a lower ability to cope with life. I encourage them to consider the thought processes in their own minds when facing a day without adequate sleep. It can lead to difficult choices, but prioritizing health is important - both physical and mental.

gdsgs

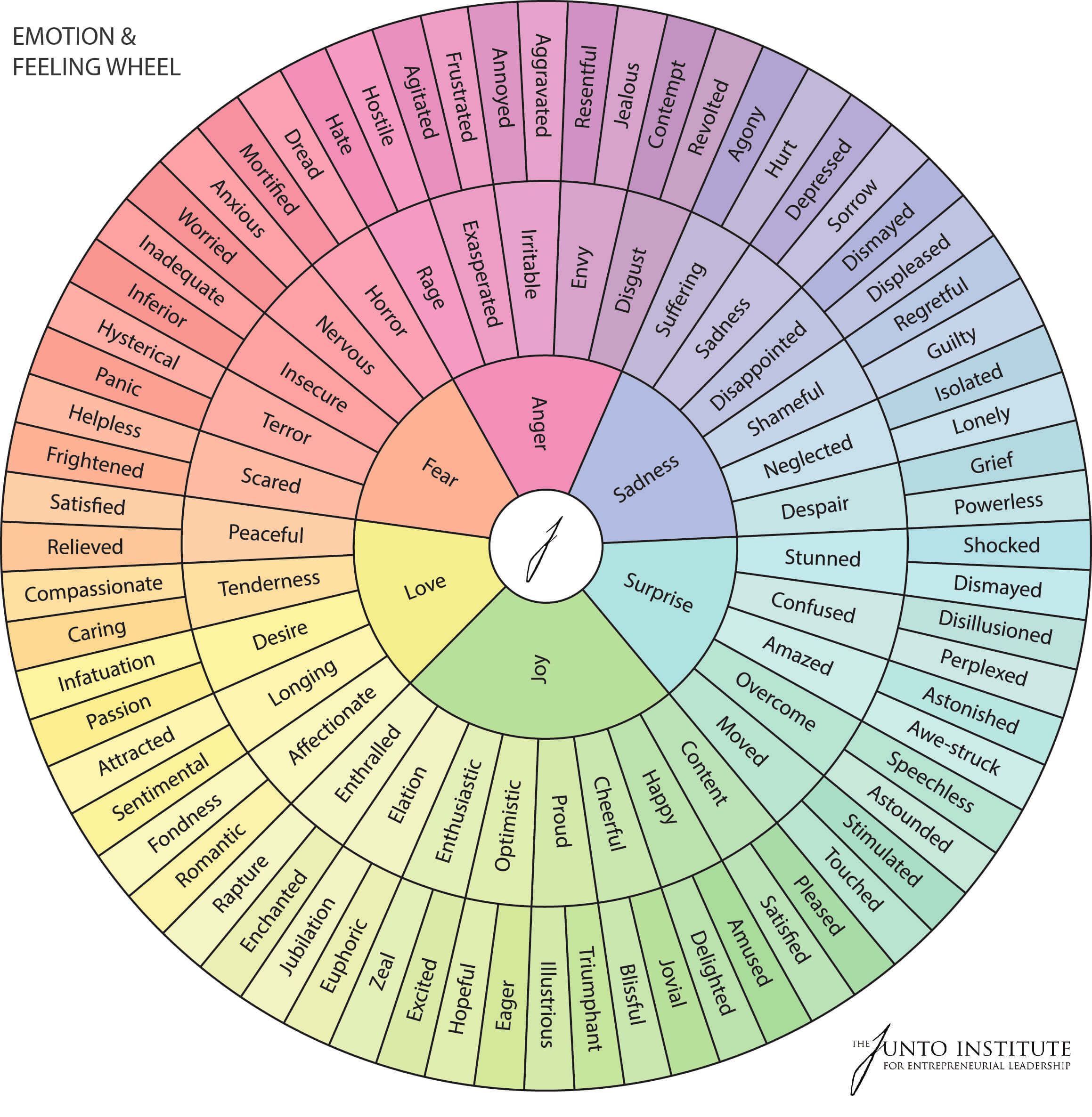

Given that my courses can be very demanding and stressful, another mini-lesson simply includes a graphic of emotional words from very simple to complex followed by, “How are you feeling about your classwork?”

Then, I encourage students to discuss their word choices with a friend or to share their concerns with me by email. Providing a range of emotional words can help students articulate more complex feelings and encourage them to consider both the positive and negative feelings they may have about a course or school in general.

Health and physical education curriculums address positive personal habits for physical health such as regular physical activity and a balanced diet. Equally important is an understanding of how we experience emotions and manage them in the complicated world that surrounds us. Everyone, at some point in life, will experience times of struggle. We will be in a stronger place to handle those trials if we have practiced mental fitness as a way of life. Just like in an emergency situation, we will be grateful for all those jogged miles.

Though my initial mission was simply to reach hurting kids, all students have benefitted from shared knowledge and skills. In conversations, students mention those lessons again and again. These activities have normalized the conversation about mental health, provided courage to battle anxiety or depression and taught tips on managing anger and frustration. Most importantly, the classroom feels like a safe place. Giving the lessons as a part of a typical instruction plan also removes bias as to “who needed it” and without attention being called to any individual.

At Rock Bridge High School, our motto is

“Where learning is for life.”

This clearly references being a person who never stops learning, but also speaks to those lessons outside of the stated curriculum which helps kids be healthier and happier people. Hopefully, the student who struggles with anxiety caused by placing a phone call to a stranger can now develop strategies to overcome it and manage the stress rather than convince someone else to do it for them.